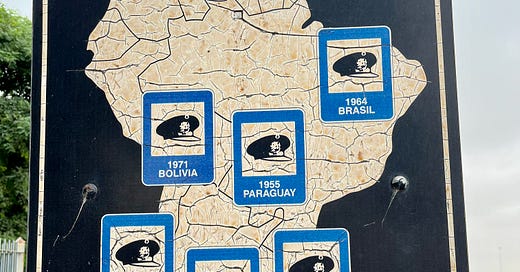

We recently went on a tour in Buenos Aires to learn more about the history and atrocities of the Dirty War, or la Guerra Sucia, where somewhere between 10,000-30,000 people were disappeared and tortured. If you’ve studied Latin American history at all, you likely know that multiple countries across Central and South America succumbed to dictatorships during the Cold War (in part supported by the US). This includes Argentina from 1976-1983.

During this time, the Argentine government specifically targeted and disappeared suspected dissidents and subversives, the majority of whom were ~18-35 years old. They were clandestinely arrested and forcibly tortured; many were killed. The government and the church denied that it was happening and families only knew that they couldn’t find their loved ones. It’s taken decades for the atrocities to come to light, and many of the perpetrators have never been brought to justice.

I knew about this period because I was essentially a Latin American Studies major (plus Advertising & Public Relations), so when I saw someone post about a related tour in the Argentina Travel Tips Facebook group, I knew I wanted to do it. And I knew I wanted the girls to learn about this history. It’s heavy, but it’s important because, as we can see across the world today, history keeps rhyming.

The tour was given by a man from England, who moved to BsAs 20+ years ago with his Argentine wife and learned the history himself. He said Argentines don’t like to talk about this period of time and many deny it happening. Take that with a grain of salt, as I don’t know what the truth is. But I do know that we have to learn about history if we hope to prevent it from repeating.

We started the tour at Parque de la Memoria, which overlooks the Plate River. You might be thinking: Oh, how peaceful and serene. Yes and no. This is where many of the bodies of those who were disappeared and tortured were dumped; I’ll cover this more in a subsequent post. The park itself at first glance doesn’t look impressive, though it does take up a lot of space. And if you don’t go with a guide, you might not get much out of the visit, especially if you don’t speak Spanish. But it has a number of signs that line the walkway near the water that tell snippets of what happened during the Dirty War. I’ve included some of them below, along with rough translations.

Sign, translated: Complicit Church | Just as there were priests who identified with social struggles — many of whom were persecuted and disappeared — there was a leadership of the church that was informed about the objectives of state terrorism and who collaborated with it. There was an agreement. There were political commitments. The military would have free rein to take repressive actions and would be supported by the Episcopate in exchange for the defense of “Western and Christian civilization” and certain privileges for the church.

The Argentine Catholic archdiocese could have stopped the genocide and did nothing about it…it helped the military appropriate and kill in the name of God. In the military vicariate [responsible for the pastoral care of Catholics serving in the armed forces], the church leaders all served as confidants to the information services and cooperated with the [military’s] repressive action. They confessed to los desaparecidos before psychologically torturing, numbing, and clandestinely shooting them. The church indoctrinated and contributed to the formation of the genocidal mentality of the Armed Forces, and it accepted the legitimacy of human rights violations. It closed the doors on the relatives of los desaparecidos and human rights organizations and ultimately supported state terrorism in all of its forms.

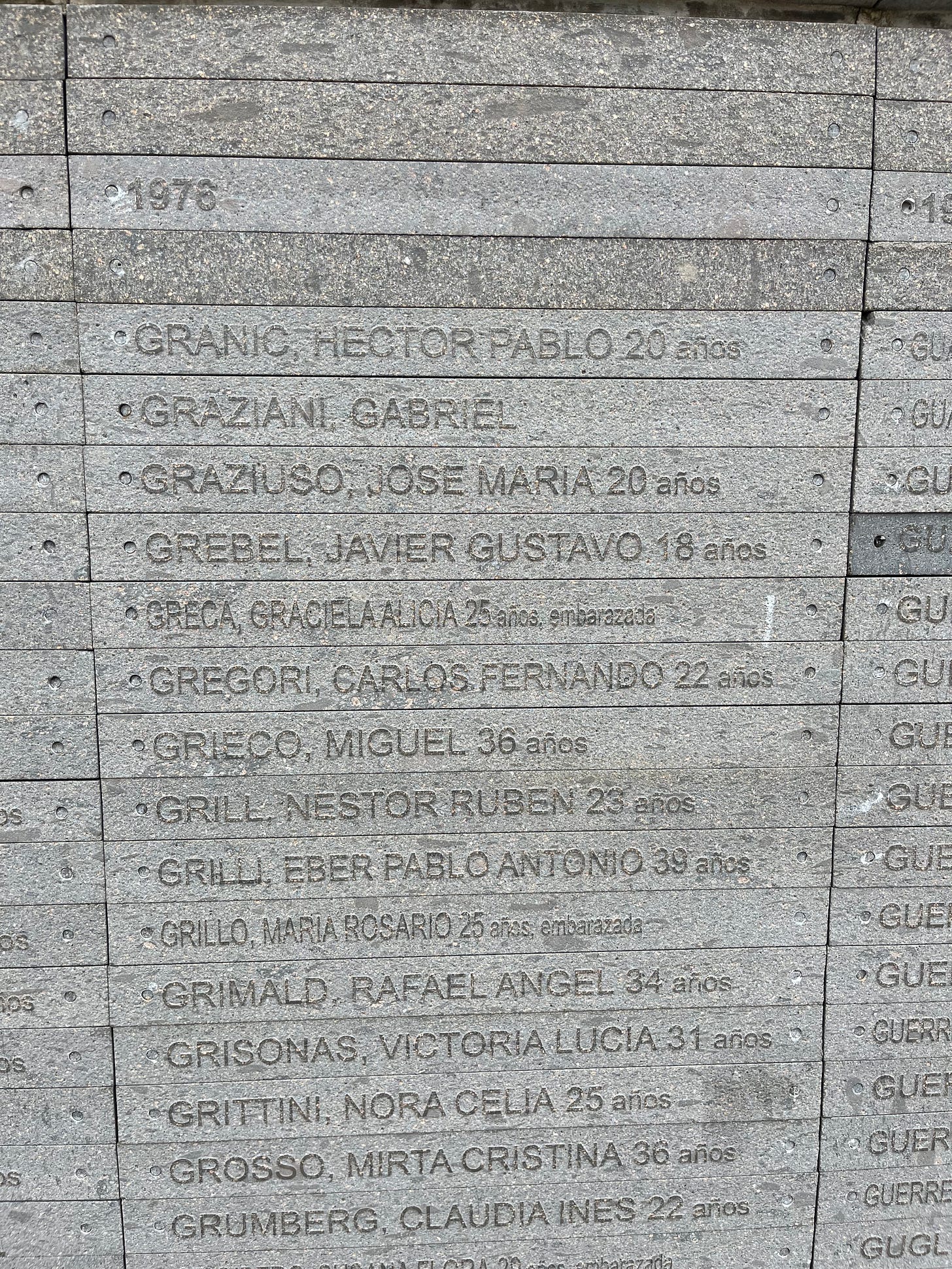

In addition to the signs, there’s a huge wall of names listing all of the known victims. In some ways it’s reminiscent of the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C., and it goes by year, with 1976 having by far the greatest number of victims. The wall memorializes not only the names and ages of the victims when they were disappeared, but also the women who were “embarazada,” or pregnant. The total tally of desaparecidos sits somewhere between 10,000-30,000 and is likely closer to the latter.

In addition to the signs and the memorial wall, the park has several art installations, at least one of which is by the son of a desaparecido.

The installation on the right says: Thinking is a revolutionary fact

Part two of the tour took us to ESMA, the former Navy School of Mechanics (Escuela Superior de Mecánica de la Armada), now a UNESCO World Heritage site. We spent quite a long time there and I’ll share a separate post or two about that experience.

For now, here are some additional resources if you’d like to delve deeper into this period of history and, of course, there’s much more beyond this. It’s heavy content but it’s really important to understand.

Resources:

Argentina, 1976-1983 (from the Holocaust Museum Houston)

Argentina (from the Center for Justice and Accountability)

Guerra Sucia: Argentina’s Dirty War (presentation put together by a teacher, I think, but provides a scannable summary for those who want bullet points)

Inside Argentina’s Killing Machine: U.S. Intelligence Documents Record Gruesome Human Rights Crimes of 1976-1983 (from the National Security Archive)

The US was complicit, not only in what happened in Argentina, but also in neighboring countries.