We were in Buenos Aires in March 2024.

As I looked at things to do and places to go in Buenos Aires, the Museo de la Inmigración kept calling to me. I’m interested in the history of other places and the stories of people. And since the US has such a rich (and contentious) history of immigration, I was curious what Argentina’s looked like in comparison. I expected the visit to be an external experience — one of learning about those who have previously come to Argentina, why, and how that has shaped the country’s history — but it turned out to be at least as much an internal one.

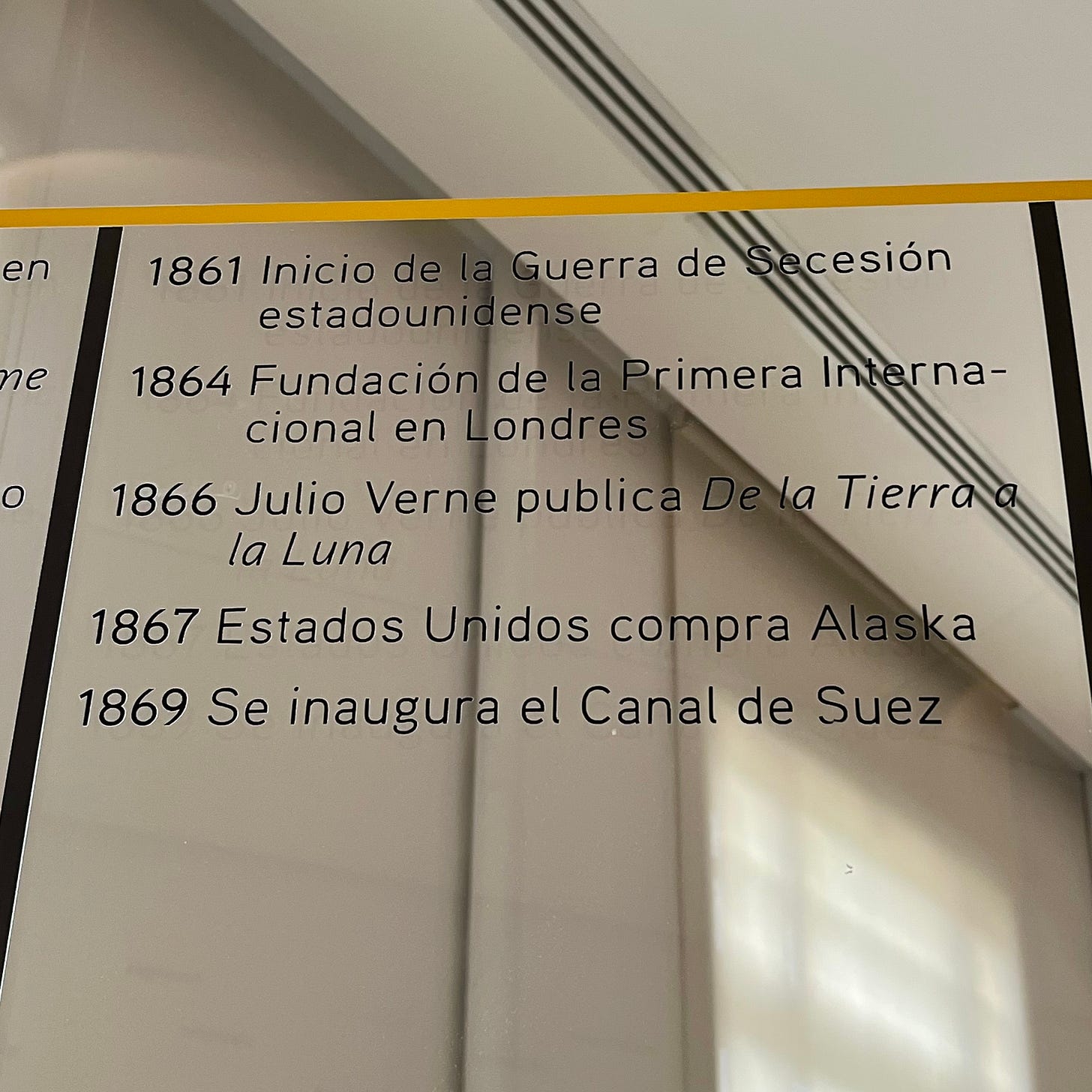

To be clear, there were exhibits depicting waves of immigrants, many coming from Spain and Italy, plus ship manifests and photos from decades ago. And there was a timeline right when you walk in outlining Argentina’s history since its independence from Spain in 1816. I thought it was nicely done, as there was a parallel timeline outlining global events.

So many glopes de estado (coups d'état). Gulp.

The museum wasn’t big and it was all in Spanish, so I’m glad I went alone, as the family would’ve been bored. I was a little sketched out being there by myself, as it wasn’t in a hip and happening part of town. It was near the port, which makes sense because it’s in the building that used to receive and house immigrants as they arrived by ship. But the area hasn’t been renovated and made part of the tourist circuit, so I felt isolated. Nevertheless, it was definitely worth the time.

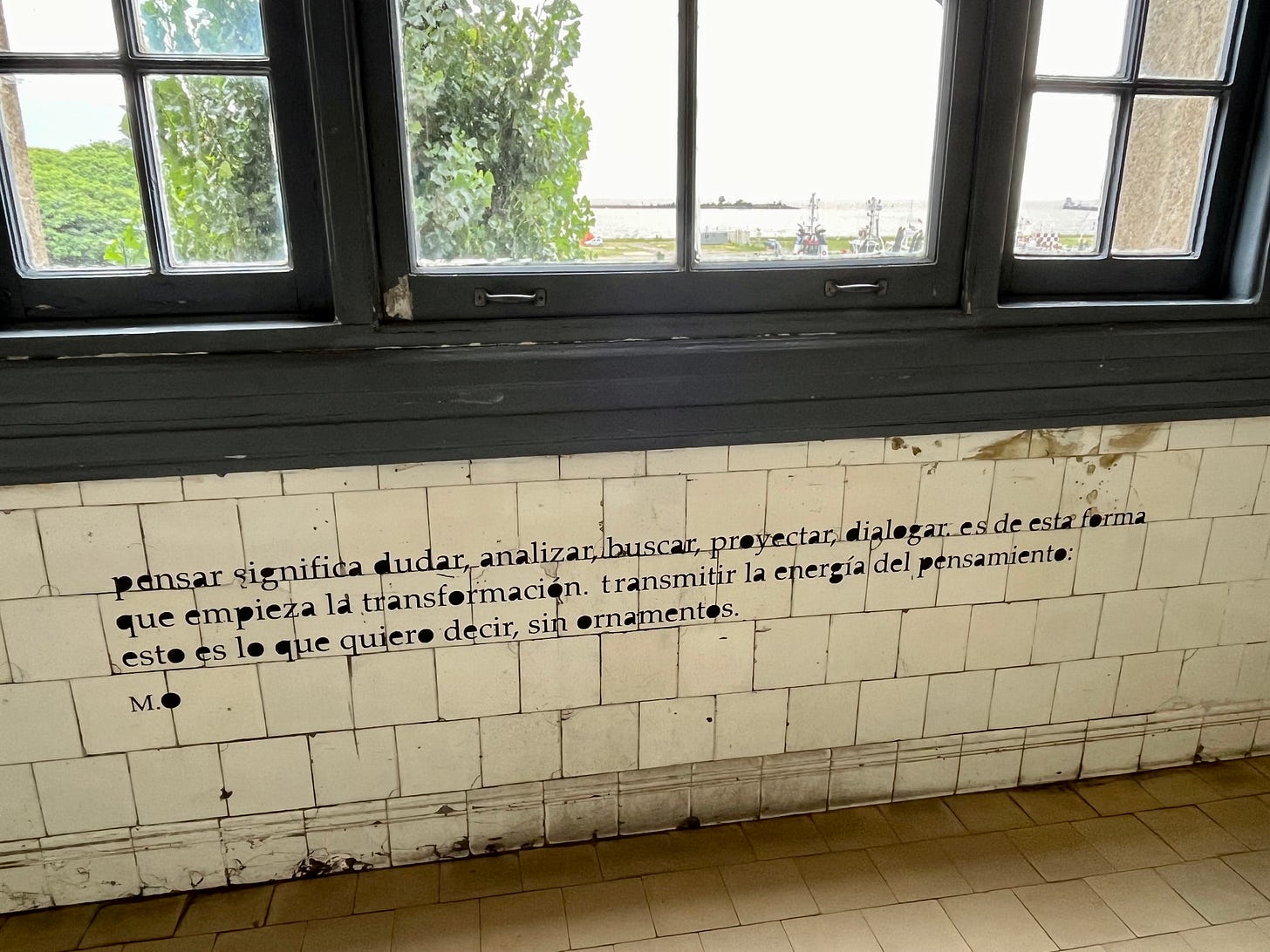

Some of the narratives on the wall pulled me in. I took a few photos and have done a rough translation in the captions below of the highlighted parts, which spoke to me.

As we contemplate living in another country for a bit, all of the decisions necessary to do so weigh on me heavily. Emigration is not a simple act of hopping on an airplane, touching down, and deciding to stay because you like the place. (Although, maybe for some, it is.) It is a legal question, an assessment in your gut, and a calculation on paper of the anticipated pros and cons of making such a distinct change in how and where you live. And with kids involved? There’s a lot at stake. And there’s no crystal ball. It keeps me awake at night (#forreal).

I think often of the immense privilege we have to even consider such a relocation. There are many parts of the world where this is a pipe dream, for any number of reasons. But our birthplace and corresponding passport open a lot of doors, as do the color of our skin and the language we speak, not to mention our financial resources. We had the good fortune to be born into most of these advantages. So many people around the world who wish for a better life don’t have these benefits. What makes their desire to emigrate from their home countries less worthy than ours? Why is immigration open to some and not to others? Of course, that’s a rhetorical question, as history in the US, Argentina, and beyond has shown that when a particular country needs a labor force, they are quite willing to let people in. And when that labor need is satisfied (generally speaking), the doors close except for those with money/means and/or connections.

The Museo de la Inmigración had a nice collection of video interviews with immigrants that you could watch and listen to.* They were deeply moving. As with immigrants to the US, people came to Argentina for different reasons. Often it was fleeing poverty or war or other challenging economic or political situations — what I’ll call running from. But sometimes it was because something — and usually someone — was pulling them towards the country — what I’ll call running towards. In general, older generations seemed to be more so running from, whereas newer generations seemed to be more so running towards.

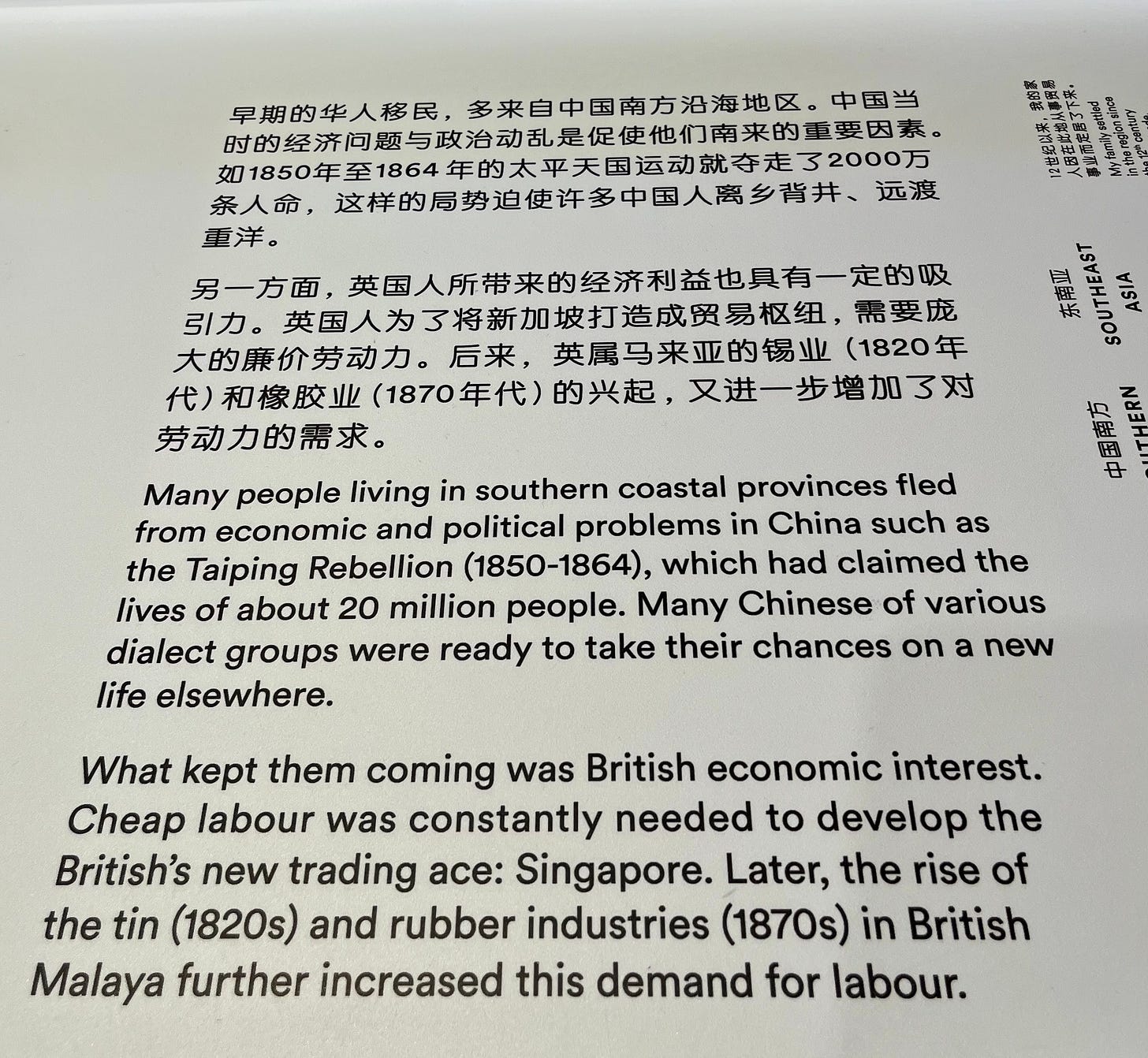

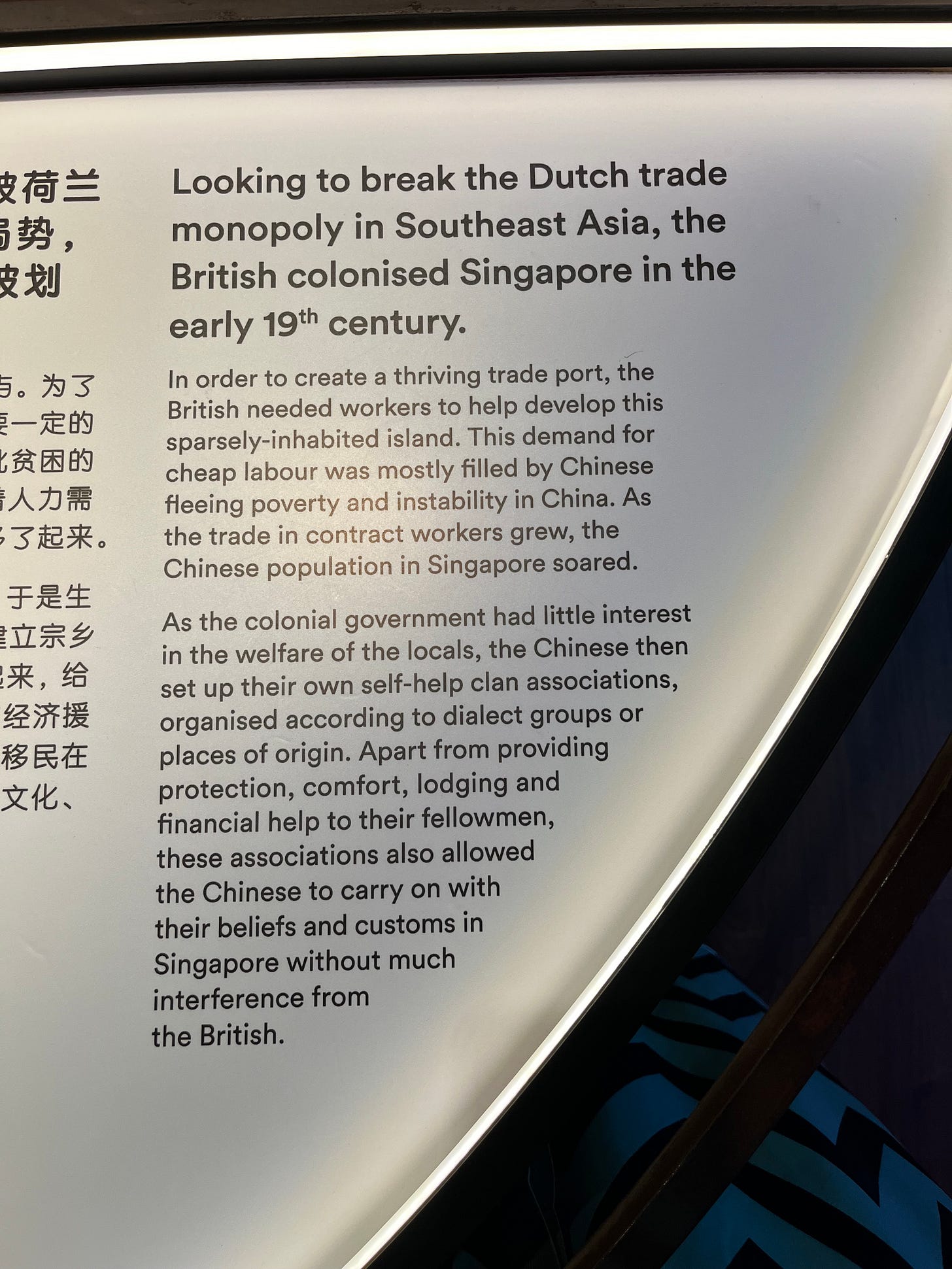

I saw similarities to what I observed at the Singapore Chinese Cultural Center that I visited in December.

In Singapore, Chinese immigration was largely from people running from poor economic conditions at home and towards the promise of better jobs. And they were being lured specifically because of an economic equation where the British occupiers in Singapore needed cheap labor.

All of this makes me think a lot about why we perhaps want to live outside of our home country for a time. It’s a combination of running towards and running from. I came of age in an era of rapid globalization, and I’ve been fascinated with other cultures and languages since at least college, where I was an International Communications major and Spanish minor. I studied abroad in Mexico and have long wanted to learn at least one more language. Twenty-five years on, though, the world — and globalization — look quite different. I’ve learned a lot about how the US has meddled in the affairs of the rest of the world. And now freedom within our home country is being eroded in ways I never imagined. Land of the free and home of the brave depends on what lens you’re looking through and what privilege you have. Some Americans have never fully benefitted from such concepts. (But that’s a related topic for another day.)

We had conversations with multiple people in Argentina (including travelers there from other South American countries) who can’t imagine why we’d want to live outside of the US; for them it’s still a mecca of freedom and opportunity. And, yes, in many ways it is when you compare it to a closed economy like Argentina’s, with a currency that has no value outside of the country. And so, as always, perspective is everything and multiple differing perspectives can be true at the same time.

Anyway, there’s lots to contemplate here. For those of you who have traveled and/or lived in countries outside of your home country, what have you observed and learned about immigration? How have your perspectives shifted (if they have)?

*******

Some additional reading:

Argentina in the Era of Mass Immigration (1880-1930) [abstract]

“There were many reasons why Europeans desired to migrate to the Americas in general, and to Argentina in particular. Most immigrants sought to leave behind the difficult economic times that led them to experience hunger and poverty, while others wanted to escape discrimination and persecution. The longing for a better life, for themselves and their families, led them to leave their countries of origin for a chance at a more promising future...These, and other incentives…made Argentina one of the largest immigrant destinations in the world during the era of mass migration, second only to the United States. It is estimated that between 1850 and 1930, Argentina received more than 6.6 million immigrants.”

Argentina’s Embedded Migrants:

…“the Constitution of 1853 specifically expressed a preference for European immigration, saying that ‘the Federal Government will encourage European immigration’ (Article 25). The use of immigration as a tool to ‘civilize’ or ‘whiten’ Argentina continued throughout the 19th Century via such iconic leaders as Domingo Faustino Sarmiento and Bartalomé Mitre.”

*******

*I’ve managed to find and link some of the videos that were available to watch at the museum. They’re in Spanish with Spanish subtitles; note that you need to turn the volume up quite a bit: